After the shōgun accidentally bowed to the wrong man because he mistook a lavishly dressed merchant for the local lord, he decreed that merchants were no longer allowed to flaunt the wealth they’d snaffled from their betters. The merchants, of course, rose to this challenge with entertaining craftiness.

If there’s one thing we all know about the samurai, it’s that they lived by a legendary code of honor. What most people don’t know is that after the Tokugawa warlords unified Japan and installed themselves as military dictators, the vaunted bushido code began to chafe a bit.

Because the same laws that ensured the warrior class would be ready to snatch up their swords and fight for their lord at a moment’s notice actually made it illegal for them to hold other jobs. They were barred by both law and pride from doing anything that might <clutching pearls> make money!

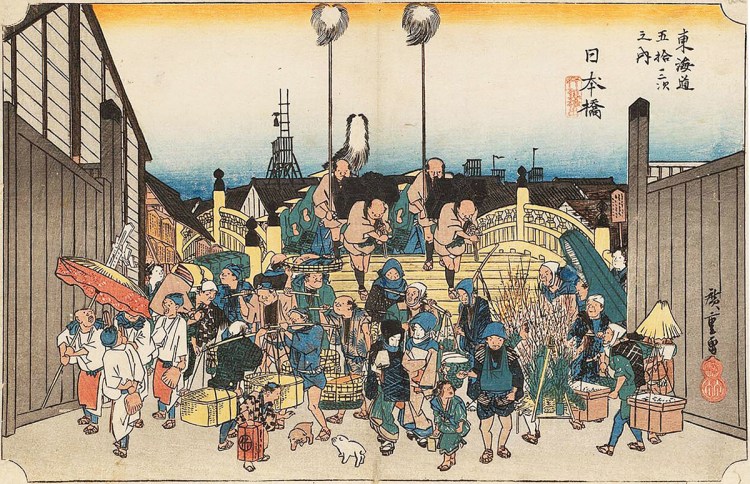

Commerce was delegated to the merchants and artisans, whose business increased hand over fist without those pesky warlords pillaging about

After two hundred years of peace and prosperity, the samurai had to stand by with idled swords while the lowest of the low became the richest of the rich. Keeping up with the daimyō next door—as well as maintaining an entire home-away-from-home in the capital*—meant plenty of samurai families ended up in debt up their eyeballs, all owed to the merchant class.

The samurai could still look down their noses and say, “Just put it on my tab” but pretty soon the merchants controlled so much of the country’s wealth that when the shōgun made one of his periodic forays to the provinces, his mistook a trader and his lavishly dressed wife for the regional ruler, and conferred honors that were rightfully due to the local daimyō. Red faces all around.

So the shōgun made a law: merchants were no longer allowed to flaunt their wealth.

Enter the fashion police

Anyone but samurai were forbidden to wear accessories adorned with gold or silver, and the merchants’ clothing had to be woven of plain, low-grade silk with no printed patterns, hand painted designs, or embroidery. Merchants caught breaking the law were fined on the spot by the fashion police.

Naturally, they took that as a challenge, not a roadblock.

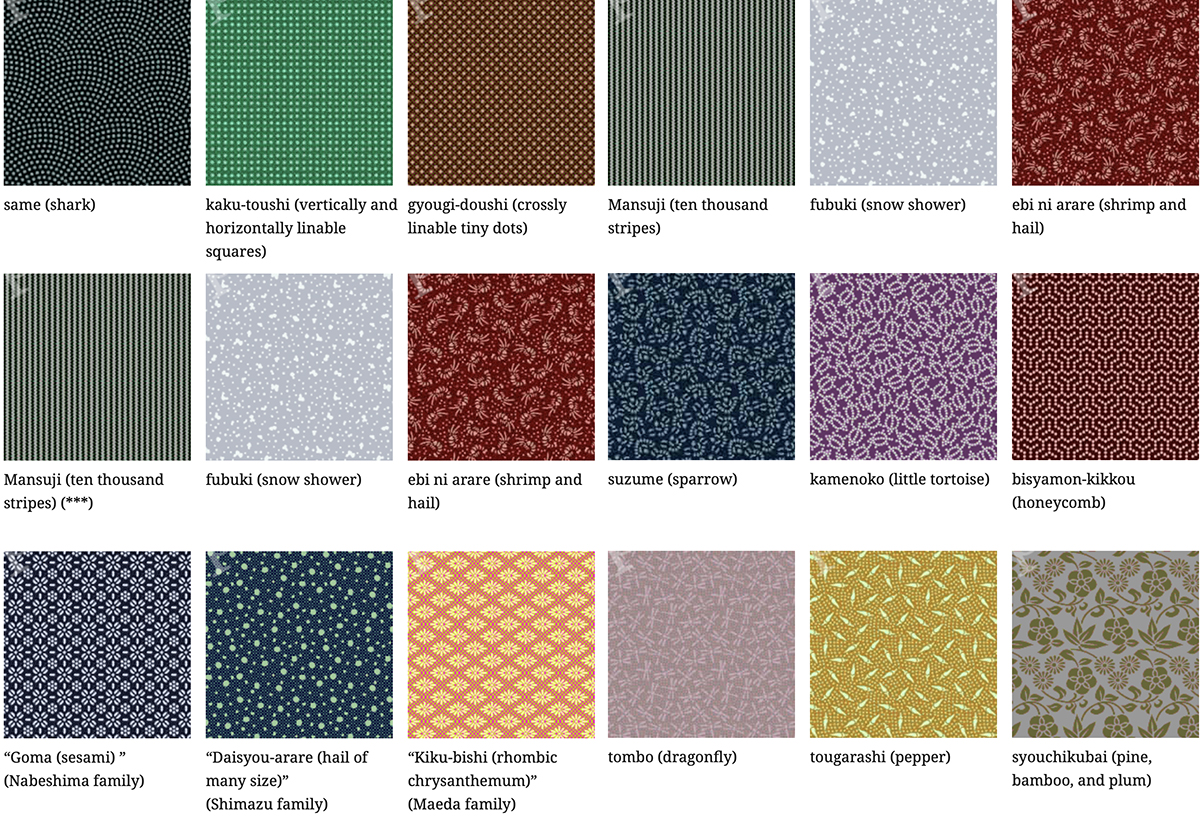

Sneaky fashion tactic #1: Edo komon is the new black

The first thing the merchants did was bring back a fashion for edo komon, which is silk printed with stencil patterns so minute they’re devilishly hard to produce and far more expensive than bolder, flashier fabric designs.

The patterns are so small and subtle that the cloth looks plain from a distance (the distance between a mounted member of the fashion police and a man on foot, for example) so the merchants could appear to be observing the letter of the law while actually thumbing their noses at authority.

This was the beginning of The Great Japanese Fashion Shift

With those holding the purse strings prizing subtlety over showiness, all of society turned to preferring the more understated aesthetic of the Japanese tea ceremony over the gold and gems and look-at-me carnival of color that had gone before. (It also signaled the beginning of the end for the flamboyant entertainers known as oiran, in favor of their understated rivals, the geisha.)

Sneaky fashion tactic #2: If you know, you know

Merchants then took a page from the playbook of the Yoshiwara pleasure quarter’s first-rank courtesans, who enticed men to spend ridiculous sums of money on them by walking in such a way as to “accidentally” display their scandalously red underrobes. Merchants copied this technique by lining their sedate kimonos with forbidden bold prints…

and vying with each other to commission famous artists to paint scenes and poems on the linings of their jackets.

Amazingly enough, this is a style that persists today—many Japanese-designed coats are all business on the outside, party on the inside!

Sneaky fashion tactic #3: Activate the artists

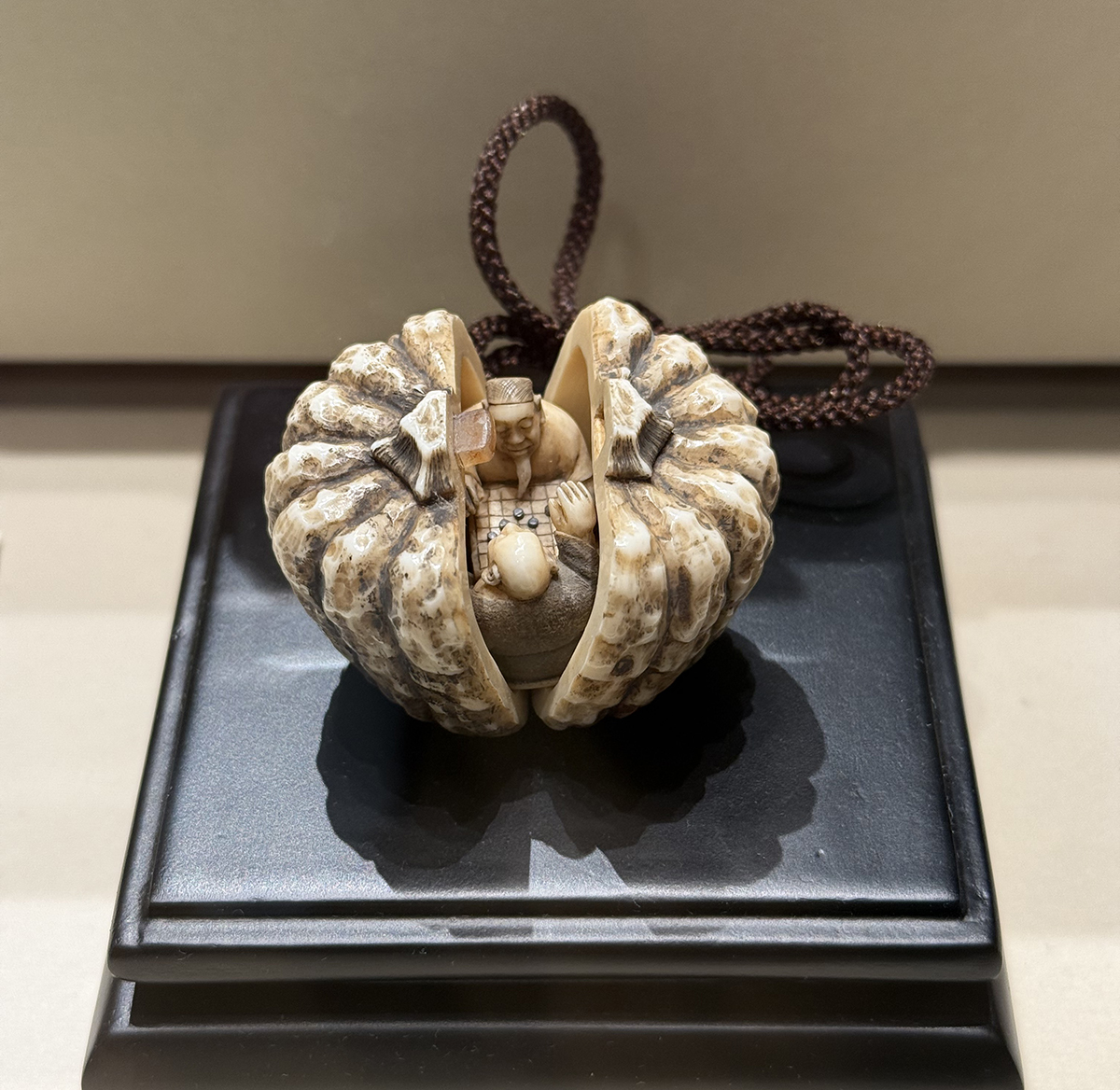

Original paintings merchants could flash at each other from the inside of their jackets were just the beginning of the unholy artist-merchant alliance. Bespoke ornaments became all the rage, with masterful carvings, rare materials, and clever designs becoming more prized than precious metals.

Enter the netsuke as a weapon of class warfare

Nowhere was the opportunity to flaunt one’s wealth with a nod and wink more refined than in the commissioning of exquisite little carvings of the beads that kept one’s inrō man-purse…

or tobacco pouch from slipping through one’s sash during a night of revelry in the pleasure quarter.

Artists began to experiment with mother-of-pearl inlay, golden lacquer and sheer artistic skill in lieu of the embargoed precious metals…

and the cleverness of the carving soared to new heights with the merchants’ willingness to pay for it.

The shift from obvious luxury to one that relied on appreciation of the wearer’s ability to combine pieces with wit and style further fueled a shift to prizing the uniqueness of the subject, clever ways to make seasonal references, and hints at the activities the wearer could afford to indulge in.

And because a man’s character could be judged by the zodiac year in which he was born, many merchants telegraphed their business acumen by making reference to the animal associated with it.

*The shōgun was a crafty old bugger, and knew that the regional warlords he’d finally gotten under his thumb would rebel the moment anyone made them a better offer, so he forced them to live in the capital city of Edo every other year. This not only allowed him to keep an eye on them, the expense drained their coffers of money that might otherwise be used for insurrection, and being absent from their home turf made it hard for insurgents to rally to the family banner in the lord’s absence. It was a brilliant strategy that worked for nearly 300 years, until a foreign warlord named Perry arrived in Tokyo harbor with his big guns and tall ships and upset the feudal apple cart.

And why do I know so much about obscure man-purses, carved beads, and secret kimono linings?

Four words: book research rabbit hole. The Samurai’s Octopus is set in the walled Yoshiwara pleasure quarter, where samurai law does not apply. All that matters inside the Great Gate is having money and spending it with style, so it’s the one place where merchants can flaunt their riches and fraternize with members of the upper class. And it’s the one place where members of the upper class can lay aside their honor and commit crimes that will stay hidden as long as they can afford to pay…

•

Click here for more The Thing I Learned Today posts

•

Or get more amusing Japan stuff sent to your email every month when you subscribe!

•

Jonelle Patrick writes novels set in Japan, and blogs at Only In Japan and The Tokyo Guide I Wish I’d Had