Discovering the sublime in objects that are

ordinary,

useful,

imperfect,

become more beautiful when well-used,

and

are made by anonymous artists

The Japanese Mingei Movement—which literally means “The Peoples’ Art”—celebrates objects used in everyday life which have been honed to perfection (and beauty) by generations of anonymous craftsmen. What makes Mingei so different from what is traditionally anointed as “art” is that every piece is useful—not merely decorative—and is made by ordinary people, not a celebrity blessed with genius.

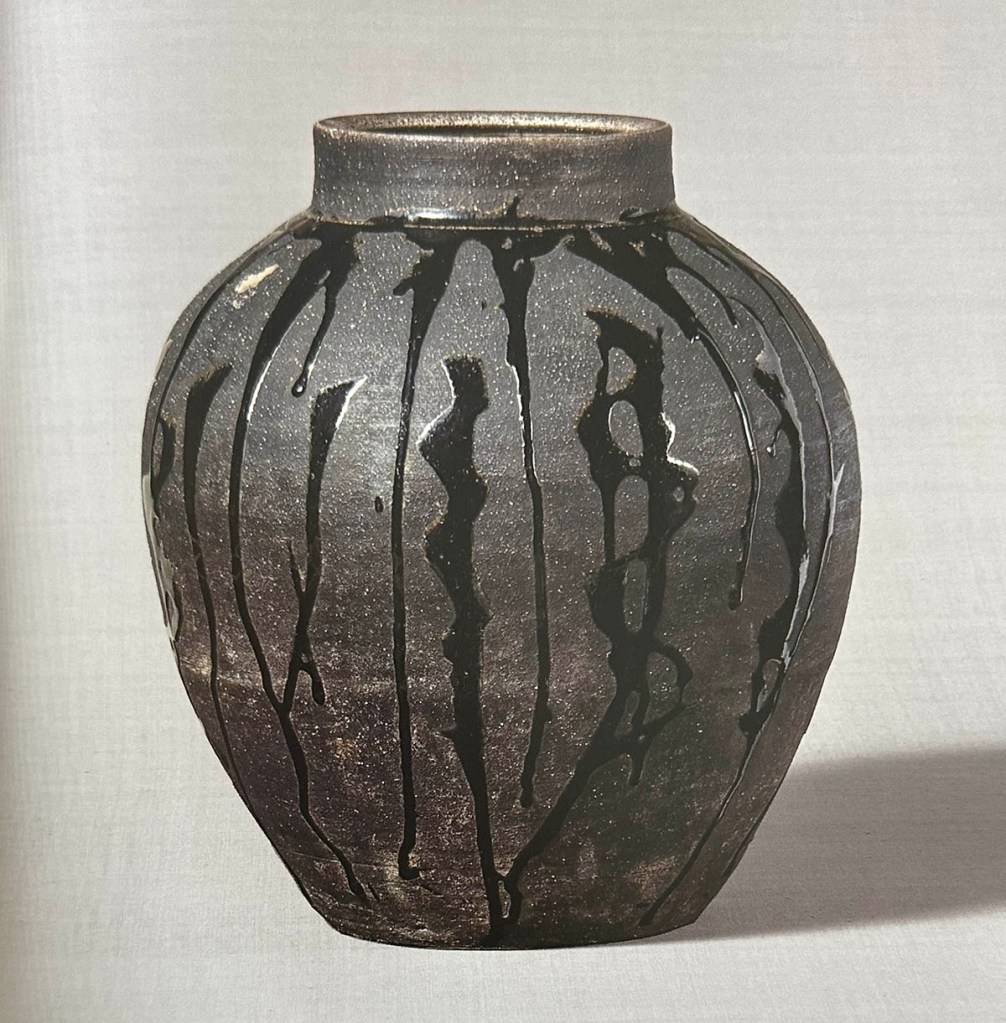

Soetsu Yanagi and his band of artists scoured every prefecture of Japan for examples of “peoples’ art” and found inspiration in everything from this traditional 19th century Shigaraki pot being sold in a second-hand shop…

to a quilted undershirt worn by Edo Period soldiers.

“Look in the now” as if seeing for the first time

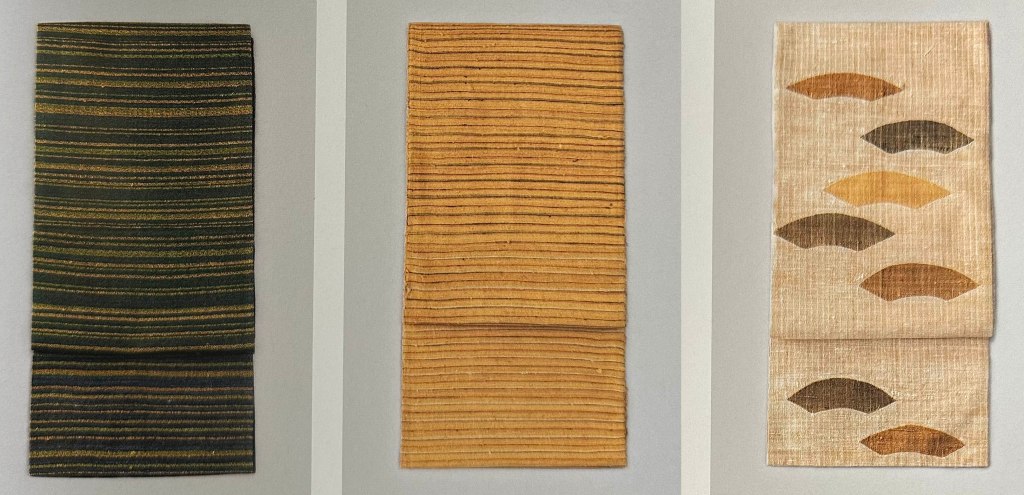

was their guiding principle. It inspired them to appreciate the intricate weaving and colored threadwork on the brooms people used every day to sweep the house…

and the irregular charm of homespun cloth.

Decorative arts weren’t excluded from appreciation, but the Mingei Movement’s favorite kind of paintings were the min-ga “peoples’ paintings”—works by amateur artists featuring popular subjects like demons, wrestlers and local landmarks.

Mingei honors a broad variety of arts, even those that require technical know-how to master

Arts like dyeing and weaving and ceramics are often relegated to second-class “craft” status in the West, but the Mingei movement appreciated that even though they share processes with mass production, they can still produce works worthy of being considered “art.”

Mingei also cultivated an appreciation that many things become more beautiful after becoming old and worn.

Mingei has deep ties to Shintoism, with its belief in gods that inhabit magnificent old things (and even today, people in Japan are wary of objects that survive for a century or more, because they may have acquired a soul). The Mingei Movement suggested that appreciating how objects show their age is a form of honoring the sacred.

They could even find the divine in mass production

Machines were taking over the manufacture of many household products in the 1920s, when the Mingei Movement started, and craftsmen had to compete by turning out hundreds of items with identical designs. The Mingei artists pointed out that the gods worked through the hands of these craftsmen in ways that machines couldn’t duplicate. Small accidents like a split in the paintbrush or inclement weather produced accidental beauty, imperfections unintended by the maker, but which made them far more sought-after than perfect specimens from factories.

Ironically, many members of the Mingei Movement became famous artists in the traditional sense, and when customers began paying high prices for their signed works, the potter Hamada Shōji was upset to hear that people were using his wares only on special occasions. He began making sets of six instead of the customary sets of five, so people could use them every day, and they’d still have a full set if one got broken.

Photo thanks to the Setagaya Art Museum exhibition catalog for “Mingei: The Beauty of Everyday Things”

The photos above are from the catalog for the current “Mingei: The Beauty of Everyday Things” exhibition at the Setagaya Museum of Art (since photography is forbidden in most of the galleries). This show is a stunning (and sprawling) presentation of the objects that inspired the original Mingei Movement artists, plus their own works, and the continuing artistry of the workshops that produce these lovely pieces today.

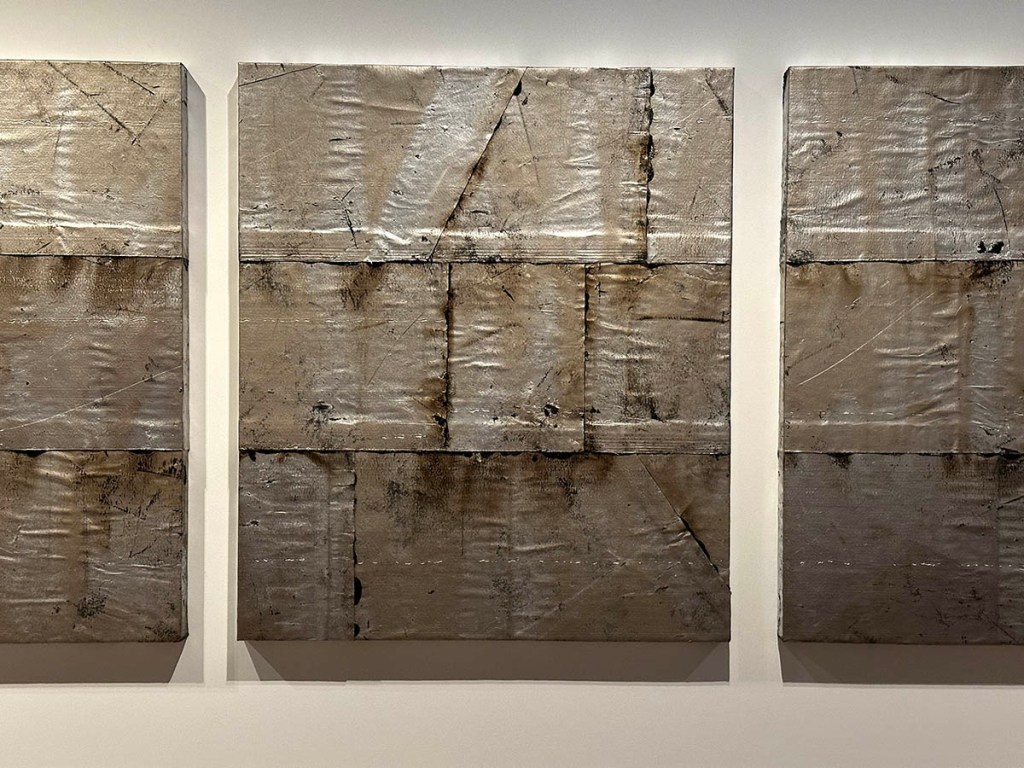

But after you spend a day with the original Mingei artists, go see the work of Chicago artist Theaster Gates, whose “Afro-Mingei” retrospective at the Mori chronicles his thought-provoking melding of Black culture and Mingei principles.

Gates has been influenced by Mingei philosophy as well as Buddhism and Shintoism since he was a young man studying ceramics in Tokoname. His work expands on Soetsu Yanagi’s principles, and points out how many aspects of Black art—church music, magazine design, and fashion, for example—are also produced by nameless artists and seldom given the honor they deserve until one looks at them “as if for the first time.”

Like the original Mingei artists, Gates elevates everyday things to high art by drawing our attention to the beauty in commonplace objects and materials we usually ignore. This series, for example, was made with roofing materials and construction processes.

Like the Mingei artists, he honors art unique to a certain place, and craft traditions that evolved in a regional style that resisted being molded or replaced by outside cultures.

In its highest and most abstract form, Gates demonstrates Mingei principles in his efforts to rejuvenate Black neighborhoods by reinserting collections from shuttered businesses and razed institutions, recognizing that those churches, banks and schools had uniquely evolved to serve that place and community, much the way that Mingei arts evolved to serve a purpose within the household, uniquely designed for the task and place they originated.

The final room in the “Afro-Mingei” exhibition highlights the shared thread that beauty and value are not defined by expense or rarity. This stunning wall displays binbō-tokkuri, which are the small flasks people who were too poor to buy a whole bottle of sake would take to the brewer to purchase amounts they could afford.

•

“Mingei: The Beauty of Everyday Things”

Dates: April 4 – June 30, 2024

Open: Every day except closed Mondays

Hours: 10:00 – 18:00

Admission: Adults ¥1700

Setagaya Art Museum

•

“Theaster Gates: Afro-Mingei”

Dates: April 24 – September 1, 2024

Open: Every day

Hours: 10:00 – 22:00

Admission: Adults ¥2000

Mori Art Museum

•

Click here for more The Thing I Learned Today posts

•

Or get more amusing Japan stuff sent to your email every month when you subscribe!

•

Jonelle Patrick writes novels set in Japan, and blogs at Only In Japan and The Tokyo Guide I Wish I’d Had